This section provides material that will support your post-Programme self-development.

‘Continuing Self-Development’ focuses on the experiential learning process that you began in the Programme and that you will continue as you develop your skills.

Or you could jump straight to the useful ‘Guide to Low-Risk Skill Practice’. Organised by Style, it provides many examples of influence use in everyday situations. Low-risk situations provide the best opportunities for pure skill practice. Combined with the work you do in moderate-risk Critical Influence Situations, your work in low-risk situations will contribute greatly to your growth as an influencer.

An imbalance of Positional power can exist in both low- and moderate-risk situations. The chapter on ‘The Positive Use of Positional Power’ will help you deal with these power imbalances whether you have high, low, or equal positional power.

‘Influence on the Run’ gives a personal account of both the pain and pleasure people experience when engaging in challenging activities. It gives ideas on how to keep your energy alive and growing as you practise your influence skills.

‘Positive Influence in Group Meetings’ discusses the use of influence with more than one person in situations where complex group issues may prevail. Both ‘Using Influence to Maintain or Build Relationships’ and ‘The Difficult Neighbour’ case study, present strategies for influencing difficult people.

Introduction

You are ready to take more responsibility for your own learning. After the Programme is over, you will be working on your own. New skills are vulnerable and you will need to nourish them carefully as you make the transition from the classroom back to work. What one learns during training can sometimes fade over time, but we do not want this to happen to you. We hope that your results will tip the other way — that you will become a stronger and more effective influencer as time goes on. You can make this happen by continuing to practise and use your skills.

You have already begun the self-development process. During the Programme, you have enriched your understanding of positive influence and have begun to practise new skills. You have set learning goals and made some choices about what to work on and with whom. In some exercises, you probably felt successful. In others, you probably felt uncomfortable with your grasp of the concepts or your ability to use them. We expect this. Both types of experience — success and failure — are important to your continued development as an influencer.

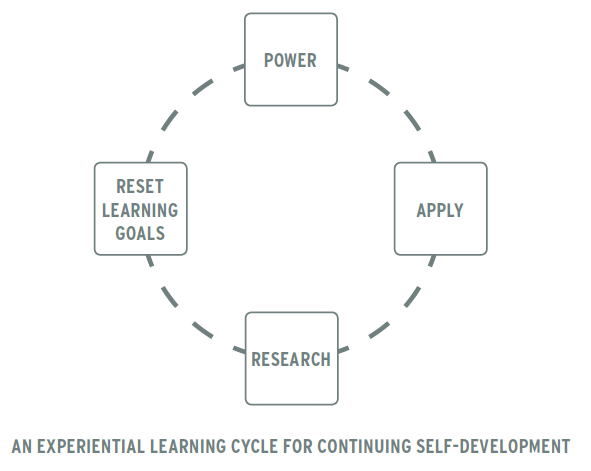

The key to successful self-development is ongoing experiential learning. The Positive Power & Influence Programme uses an experiential learning process. You test and refine new skills as you apply them. By carefully planning your influence attempt, consciously applying your skills, and thoughtfully researching the results, you can revise your learning goals and plan for the next round of application. This process will accelerate and support your growth as an influencer. You learn how to learn about positive influence in the process of influence itself.

Your success will depend on continued experiential learning in real-life situations. Skills fade without practical application: ‘If you don’t use ’em, you’ll lose ’em.’ In this section we explore ways you can sustain the experiential learning process after the Programme is over.

Success factors in Experiential Learning

When you return to work, you will face the challenge of choosing appropriate situations for practicing influence skills.

These situations will range in difficulty. Some will be easy situations in which your chances of success will be high. Others will be difficult situations in which your chances of success will be lower. The perception of an influence situation as easy or difficult is highly personal. What one person may think of as an easy situation, another person may think of as extremely difficult, stressful, or demanding.

You can determine the relative difficulty of an influence situation by assessing two factors: external risk and internal stress. By understanding and evaluating these factors, you can assess your chances of success in influencing others.

- External risk depends on the personal stake you have in the situation.

If your personal stake or investment in the situation is small — if you have little to gain or lose — your external risk is low. If you have a lot to gain or lose, your external risk is high. You can determine your degree of external risk by analysing the situation, measuring the gains to be made by reaching your objective, and assessing the degree of personal power you will gain or lose based on the result.

- Internal stress depends on your discomfort in using the Style.

In the Track exercises, you developed personal data on how you feel when performing each Style. You identified specific barriers — skill gaps, value conflicts, and blocks — that interfered with your performance. Since you performed these exercises in the relative safety of the workshop environment, your external risk was low. There was little or nothing to lose if you performed them poorly. Internal stress caused most of the difficulties you may have experienced.

Be realistic about the influence situations you will face. Carefully assess your external risk and internal stress. Assessing your external risk will help you determine the benefits or potential gains to be achieved by conducting the influence attempt.

Assessing your internal stress will help you determine the costs or difficulties involved in conducting the influence attempt. You can then do a traditional cost-benefit analysis to decide whether to go ahead with your influence attempt or find a better situation where you can practise.

The key to continuing self-development is ongoing experiential learning. This requires choosing appropriate situations for practicing influence skills. The appropriateness of a practice situation depends on two factors: your external risk and internal stress. Keep in mind that:

- High-risk situations are not appropriate for practicing influence skills. Disengage from these situations until you have achieved Style mastery.

- Moderate-risk situations are best for practicing influence skills.

- Low-risk situations are good for repetitive skill and practice.

- Low-stress situations provide good opportunities to internalise your learning and make it automatic. If your risk is too low in these situations, consider increasing it. If your risk is too high, consider decreasing it.

To make the most of your experiential learning efforts in moderate-stress/moderate-risk situations:

- Plan your influence attempt, using the Five-Step Planning Process.

- Apply the Style and stretch its limits.

- Research the results of your influence attempt to determine the value or benefit of correct Style use.

- Reset your learning goals for your next influence attempt.

If you face a high-risk situation early in your development, disengage from it!

Defer acting until you feel more comfortable using the Style.

This will occur sooner than you think. As you gain experience and skill in using the Styles and Behaviours, your stress will diminish. The number of situations that you find moderately but not highly stressful will increase.

Assess risk more objectively over time.

The personal stake that you have in a situation may not change, but your level of self-confidence in handling the situation will increase. In some cases, you will attain a degree of detachment from the situation, since you know that there are many optional ways of handling it. As a result, your personal stake in the situation may even decrease.

Include risk management as part of your plan.

You will learn to moderate risk by carefully analysing the influence situation and setting more manageable, achievable objectives. You will learn to think more tactically about applying influence and become more adept at Disengaging to manage tension. Consulting and rehearsing with others will have a dramatic impact on your risk level and allow you to see the situation more objectively.

Moderate-stress/moderate-risk situations are the most productive for experiential learning. When honing your influence skills, choose situations that are neither too easy nor too difficult. By picking situations where your stress and risk are moderate, you can challenge your abilities without endangering yourself. You have already engaged in moderate-stress/moderate-risk situations in the Programme, and you should seek additional opportunities after the Programme concludes.

Here is how you can make the most of your experiential learning efforts in moderate-stress/moderate-risk situations:

- Plan your influence attempt.

Use the Five-Step Planning Process to provide structure and to support your continuing development. Rigorous and disciplined planning is important for sharpening your influence skills. Planning will help you to identify various Style issues and force you to consider Style alternatives. It will enable you to choose the most appropriate Style for the situation, given your current skill level.

The Five-Step Planning Process instructions will give you information on dealing with moderate-stress/moderate-risk influence situations. The five steps will help you to control your risk and stress levels and get the most out of the experiential learning process. Once you master the moderate-stress/moderate-risk situation, you will be able to try your skills in more difficult situations.

- Apply your skills.

Once you are in the influence situation, focus and concentrate on your performance, try new Behaviours, and stretch the limits of the Style.

- Research the results.

After your influence attempt, assess the actual results against your performance. This will help you to determine the value or benefit of correct Style use. It will reveal shortcomings to remedy in your next influence attempt, as well as constructive and practical ways to modify your behaviour for greater success.100

- Reset your learning goals.

You can make decisions about future self-development activities more confidently after you have obtained results, identified your shortcomings, and specified ways to improve your performance.

As you engage in moderate-stress/moderate-risk situations, you will notice specific Styles and Behaviours requiring repetitive drill and practice. Moderate-stress/low-risk situations provide perfect opportunities for this type of skill development. You have engaged in some moderate-stress/low-risk situations in the Programme, such as the Track exercises.

We ignore hundreds of potential moderate-stress/low-risk situations daily. Either the situations themselves are not important, or we find ways to meet our needs elsewhere. Perhaps we fear the consequences of failure, or we feel too tired or distracted to act.

Here are some examples of moderate-stress/low-risk situations:

- People who are chronically rude or discourteous.

A clerk at a local store who is always rude or uncooperative provides a perfect opportunity for skill practice. You have nothing to lose — how could this person’s behaviour possibly get any worse? Use positive influence to change the way this person treats you.

- Bureaucrats who treat you impersonally.

All of us make assumptions about what is acceptable behaviour in certain situations, based on our experience or arbitrary rules set by others. Rarely do we question our assumptions. For example, do you assume that a queue for a ticket agent at an airport check-in counter always proceeds in order of arrival? Do you think that an express checkout line at a supermarket strictly enforces the ‘number of items’ rule? Simple observation will tell you that these assumptions are not always true. People bend the rules. Use positive influence to get treated well, according to your needs.

- Annoying everyday situations in which you routinely suppress your needs.

Lack of experience using personal power and influence can increase your sense of powerlessness in many situations. Practise your positive influence skills on people who talk during a movie, smoke in a nonsmoking section of a restaurant, or cut ahead of you in a checkout line. You will suddenly recognise that you can change the little annoyances that whittle away at your energy during the day.

We have talked about practicing influence skills in low-risk situations. What about practicing influence skills in low-stress situations?

Most participants long for the day when they will respond automatically to influence situations with the right Style. This will happen soon if you continue to implement the experiential learning cycle.

Low-stress situations provide good opportunities to internalise your learning and make it automatic. The most important point to remember in low-stress situations is to manage risk.

- If your risk is low, consider pursuing a more ambitious objective.

When you can use the Best Style for the Objective (BSO) comfortably and confidently, you are approaching a level of competence that supports greater risk-taking. If you have chosen an undemanding objective, be alert for the possibility that you are Avoiding — taking the easy way out. By limiting your objective, you may be cheating yourself of the opportunity to ask for more or to develop a more constructive relationship with the influence target.

- If your risk is high, use the Five-Step Planning Process.

Careful and detailed planning will help you to control risk. Consulting and rehearsing your Action Plan with others will enhance your chances of success. Beware of the tendency to reduce your expectations in high-risk/low-stress situations. This would be Avoiding.

A Guide To Low-Risk Skill Practice

Some situations are better than others for practising new influence skills. This guide is designed to help you identify these situations in your everyday life. It includes guidelines for choosing practice situations, examples of practice situations, and short exercises to try for each Style. We encourage you to find opportunities to practise that fit your particular needs.

Guidelines for choosing practice situations

Most people feel a little uncomfortable when practising new skills. Your discomfort is likely to increase when you practise in situations where there is something significant to lose (high-risk). It can be painful and frustrating to try new behaviours in chronically difficult relationships with family members or to remedy long-standing problems with co-workers (high-stress). Certain business situations may be too tense or conflict-laden to qualify as good practice opportunities (high-risk and high-stress). Insecurity, stress, and fear of failure will make it difficult for you to do a good job. In such situations, you will probably avoid using the new skill altogether.

Low-risk situations are best for pure skill practice. By reducing or eliminating risk, you can concentrate on improving your performance. While your stress level may be high there is nothing to lose objectively in such situations. Soon you will experience success. Success will increase your competence, build your self-confidence, and reinforce your desire to keep practising and improving.

In general, choose practice situations where:

- Your expectation of success is high and your fear of failure is low.

Although some of the ‘practice targets’ will be strangers others will be old friends. Practise in situations where there are few, if any, barriers to success. Disengage from critical situations where serious consequences might result if you fail to influence the target on your first try. These situations will require a full process of planning and rehearsing.

- You can specify an Influence Objective.

Do not seek vague or general agreements from targets. Do not stop when they have superficially accepted your position. Go further, and get their commitment to a specific next step. Decide who will take the step and when. The extra effort can make the difference between success and failure.

- You can get clear and immediate feedback.

Practise in face-to-face situations where you and the target decide the outcome very quickly. Complex situations that drag on for a long time are the least helpful for practising new behaviours.

- You intend to carry out agreements.

Do not play at influence skill practice. Failure to carry out agreements is the weakest way of exerting influence. Listen for and be aware of the small inner voice that tells you not to follow through if you can avoid it. Force yourself to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ aloud to the target’s position. This will require you to develop your own position and defend it. Disengage if you need time to prepare your position, then return to the situation later.

- People will not be surprised by a sudden change in your behaviour.

Although some ‘practice targets’ will be strangers, others will be old friends. If you change your behaviour without warning those who know you, they may think you are unpredictable and react with discomfort, suspicion, rejection, or attack. This can happen even when others have asked you to change. Human beings like being able to predict how other people will act. When practising new skills, inform people of your intentions and ask for their help.

Situations that fit these guidelines might include:

- Interactions with friends, colleagues, or others with whom you have good relationships. You should feel comfortable explaining to them what you are doing and enlisting their support and feedback.

- Less important interactions of limited duration with tradespeople, service and professional personnel, and strangers.

- Minor conflict situations in which neither party has a big stake, including isolated transactions with limited consequences for the future of the relationship.

- Joint problem-solving situations where neither party has a strong vested interest and both you and the target are open to alternative perspectives and solutions. These situations might include deciding where to go to dinner, setting specifications for purchasing a new piece of office equipment, determining how to format a report, and so on.

The following pages list examples of situations that support the low-risk practice of Influence Styles and Behaviours. Use these examples to stimulate your thinking and to identify practice situations of your own. Practise opportunities that you identify will be as valuable (or perhaps more so) than the ones we suggest here.

Low-Risk Skill Practice – Persuading

There are so many opportunities to practise Persuading in business and professional situations that it is easy to overlook them. Doing business as usual may cause us to miss important practice opportunities. Look for specific opportunities, develop concise Influence Objectives, and focus on practising a specific Behaviour. Push yourself to go a little further than you normally would in performing at least one aspect of the Style.

- In meetings, offer suggestions that you normally might withhold.

Make straightforward proposals and support them with strong reasons. Structure the meeting by suggesting an agenda. Use hard data to summarise your thoughts on a particular issue.

I suggest that we change our procedure by setting an agenda. That way, we can see what work we need to do. We can also set up a specific plan to use our time efficiently.

- Respond objectively to suggestions or proposals.

If you disagree with someone’s proposal, give your reasons and make a counterproposal. If you agree, give clear reasons for supporting the proposal.

I see that differently. I suggest that we continue without an agenda. The data about our regular work groups says that too much structure reduces creativity. We need to remain open to new ideas since the old ones just aren’t working. After all, our profits have fallen 23 percent because we haven’t come up with any recent innovations.

- State your proposal first.

When opinions are sought or the floor is open for ideas, be the first to speak up rather than waiting until everyone else has spoken.

I have an idea! Let’s develop an agenda but leave time at the end of the meeting for brainstorming. My thinking is that we can do both. An agenda will help us to structure the meeting. A brainstorming session will let us get all of our creative ideas out in the open.

- With salespeople or managers, suggest changes that will make you a happier customer.

I notice that you have the display of new books behind the counter. I suggest that you place it in front of the cashier’s line. I like to browse, and it gives me something to do while waiting my turn. Also, if I pick up a book, there’s a greater chance that I’ll buy it.

- Suggest additions or deletions to the standard product selection and give reasons for your suggestions.

I propose that you carry the manual model of that car in addition to the automatic. Automatic transmissions are often less fuel efficient, and manual cars handle better in bad weather. Besides, some people don’t like driving automatics, and you’ll sell more cars if you carry both models.

I suggest that you stock red leaf lettuce as well as iceberg. The iceberg variety is less nutritious than red leaf and having both will give your customers more choice.

- Answer truthfully when asked, ‘Is everything all right?’

Respond succinctly, suggesting specific changes that you would like made. Point out unsatisfactory service, merchandise, or decor. Give reasons for your suggestions.

The waiter served us promptly, but he only took our beverage orders before he left. I suggest that you tell him that many of us who come in for lunch are in a hurry. It would be a good idea for the staff to take the entire order at the very beginning.

I think that you should turn up the thermostat a few degrees. I’ve already put on my sweater and I’m still cold. I see that others are bundled up, too.

- If you do not like something, suggest a specific improvement.

I suggest that you move this table over by that wall. It’s only three feet away from the service bar, and two people have tripped over my chair since I sat down.

Perhaps one of your supervisors can take over at another cash register until the rush is over. The checkout lines are very long and getting longer. Your employees look unhappy, not to mention the customers. I saw two people put their merchandise down and leave the store.

- Persuade a service-provider to do something for you that is sensible but not the norm.

I have a different idea. Deliver the new sofa to me later in the day. That way, I’ll be here to let you in. You won’t have to make a special phone call to see if I’m home yet, and you’ll reduce the risk of having to come back.

I suggest that you hold these items aside for me until I can return with the exact measurements. It doesn’t make sense for you to show me other models until I know which size will fit. Besides, once I have the measurements, I can analyse your recommendations more objectively.

- Ask a service-provider to personalise a job for you.

Please butter my toast in the kitchen. That way, it’ll melt faster and be much easier for me to spread. You’ll also waste less butter.

I suggest that you return this fixture and get a chrome finish. This one is sturdy enough, but it doesn’t match the other fittings. Also, you told me yesterday that chrome fittings are more accurately machined and easier to work with.

- Question the advice and opinions of experts.

Ask physicians for information on medications that they prescribe for you. Ask automobile mechanics what repairs they intend to make and why the repairs are necessary. Experts are not infallible. Do not avoid making choices by letting experts and professionals choose for you. Instead, get the expert to give you enough information so that you can form an opinion and decide for yourself. Persuading is not one-sided. The target should also convince you.

Doctor, I suggest that you write me a prescription for that new medication for migraines. The one I’m taking now makes me sleepy, and I understand from my reading that the new one has fewer side effects.

Listen, before you go ahead and order a new set of windshield-wiper arms, why don’t you try thoroughly lubricating the springs? That way, we’ll test the easy solutions first. Besides, I recently read that the wiper springs are the part least likely to be serviced in the entire car!

- Express an intellectual opinion at least once when discussing topical subjects.

Use supporting facts. Voice your agreement or disagreement clearly. Do not be pushy or argumentative, just communicate your thoughts. It will help liven up the conversation.

Studies show that good posture at the table aids digestion. The research also suggests that you’ll feel less full and be more energetic after eating. Good posture also sends a message that you like the people around you and that you’re interested in talking with them.

- Develop and express logical opinions about issues, even when the issues are complex and you are unsure your opinion is well-founded.

Those who talk the most and loudest do not necessarily have all the correct facts either. Decide which way you lean on issues, then identify two or three good reasons for your position.

There are five classic films showing in town and we can’t see them all this weekend. I suggest that we pick the one we’d really enjoy seeing in a theatre. We can always see the others on video. Besides, you’ve always said that ‘Gone with the Wind’ was meant to be seen on the big screen, not television.

- Persuade a family member to do a small task for you.

The task should be something that the person might not volunteer to do but does not fundamentally oppose.

- Use Persuading instead of ‘I don’t care.’

Consider this exchange:

Would you like to have the Smiths over for dessert and coffee tonight?

I don’t care.

We almost always do care and have an opinion, but rather than think about it, we avoid. Try Persuading instead:

I suggest that we invite the Smiths over tomorrow night instead of tonight. I’d like to visit with them, but we have to be up early tomorrow. I’d also like to prepare a special dessert for them, and I won’t have time today.

- Listen to how you express agreement or disagreement with other people’s suggestions and proposals.

Do you state your position and give the reasons straightforwardly? Or do you make emotional evaluations of their positions, dismissing them as wrong or stupid?

Do you sound like this:

I can’t understand how you could wait so long! The facts are clear. There are only four days remaining until the filing deadline, and you have a full year of tax receipts to go through!

Or, do you sound like this:

I suggest that you go through the tax receipts first. There are four days left until the filing deadline and, if you do that first, you’ll have a much better idea of whether or not you’ll need to ask for an extension. You can plan for all the possibilities.

When Persuading, try to keep your opinions free of judgmental language.

Low-Risk Skill Practice – Asserting

- Before a meeting, clarify your personal wants and needs.

Focus your attention on what you want the group to accomplish: items to discuss, issues to clarify, decisions to make. Write a personal agenda. Begin each item with the words ‘I want…’ or ‘I need…’ Keep track of the number of times you make your wishes known and move the meeting through your personal agenda. Take initiatives!

I want five minutes to discuss this problem.

I need to cover the inventory question today.

- Try saying ‘no’ when someone asks you to do something that you would rather not do.

Saying ‘no’ does not necessarily mean that others will think you are uncooperative or rude. If you say ‘yes’, try to bargain or negotiate for something in return.

I can’t help you right now. I’m too busy. But if you’re willing to substitute for me at this Thursday’s conference, I’ll handle your job then.

- Encourage people to consider personal as well as rational issues when making decisions.

Very often, people base decisions on logic and not on the personal needs of the parties involved.

I want to look at this from another perspective. I like the logic of your proposal. I’m not pleased that my department will be doing most of the work. I need to talk to you about how this affects me personally.

There are many opportunities to make legitimate statements of personal need or desire in commercial situations. Persevere. If the target resists or evades the issue, offer personal incentives for what you are demanding. If the target continues to resist, bargain or use a pressure. Remember to use incentives and pressures that you personally control. Be assertive and not aggressive. Recall that, with Asserting, you may not get what you want, but others will rarely dismiss you lightly.

- State your requirements clearly.

Ask salespeople for what you want, rather than search for the item yourself. Then, ask to see something bigger, smaller, cheaper, or in a different colour.

I want you to special-order these styles in my size. I like your selection, but I’m upset that you don’t carry my size. If you’re willing to order it so that it arrives by the 15th of this month, I’ll become a regular customer.

- Return something you dislike.

Ask for your money back. In restaurants, return food that does not taste good or ask the chef to prepare it differently.

This sauce has an unpleasant aftertaste. Please take back my plate and give me a steak without the sauce.

I don’t like the colour of this shirt in outdoor light. I want to return it and get my money back.

- Ask for a price reduction for buying a larger quantity or for not using your credit card.

I’ll take four of these now if you give me a 10 percent discount.

I’ll buy this if you will give me 5 percent off for cash.

- Ask for what you want instead of settling for the standard offer.

Request a different table, clerk, hair stylist, hotel room, another seat at a formal event, and so on. In a restaurant, ask for something that is not on the menu. Or ask a nearby employee for help rather than waiting for your assigned waiter or waitress.

- Request a change that will improve the atmosphere or climate.

Ask someone to lower the music volume, increase the heat, turn off the television, and so on.

If you agree to keep the heat turned up a few more degrees, I’ll pay 5 percent more than my usual share when the bill comes next month.

- Ask for redress of minor wrongs.

This includes poor merchandise or service, an improperly done job, overcharging, or shortchanging. Try not to worry about whether you win or lose — it is all good practice.

I want you to take back this shirt and give me credit for it.

This receipt shows £5 for something I didn’t buy. Please correct this error.

- Try Asserting in money matters, especially where there is no fixed price or standard of value.

While the seller has the right to set a price for merchandise or services, you have a right to offer what it is worth to you. Suggest a smaller figure than what the seller asks and see what happens.

I find this suit very attractive, but £30 is not enough of a discount. Increase the discount to £50 and I’ll buy it.

I want this salad but without the fish. Please take a few pounds off the price.

- When someone annoys or offends you, ask that person to stop.

Ask a person who cuts ahead of you in a checkout line to move back, or ask the cashier to serve you next. When people talk during a film, use positive influence to let them know they are disturbing you. When sales people are inattentive or rude, point this out to them.

I don’t respond to high-pressure selling. If you want to make this sale, please give me time to take your proposal home and think about it.

This is the last time I’ll ask. If you don’t stop whispering during the movie, I’ll call the manager and ask him to handle the problem.

- Take the initiative when making decisions.

Express your wishes, goals, suggested courses of action, or preferences before asking for the other person’s opinion.

Instead of asking: What would you like to do tonight?

Say: I feel like going out to dinner tonight instead of cooking. I’ll call the restaurant, make the reservations, and drive us there.

- Do not automatically go along with other peoples’ suggestions.

If you prefer a specific alternative, say so, though you may have to compromise or concede later. The other person may be willing to do it your way.

I don’t feel like going to the movies tonight. I want to stay home and play cards instead.

- Give yourself permission to change your mind after agreeing to something.

Without going back on your word, you can still describe how your feelings have changed or how circumstances have altered. Then ask the other person to let you out of the agreement. Of course, it is usually better to disagree before committing yourself. But often people who are just beginning to use Asserting do not find out that they mean ‘no’ until after they have said ‘yes’.

I’m not able to go to lunch with you tomorrow. I enjoy your company, but going out will prevent me from completing an important project. Getting it done is also important to me. If you give me a rain check, I’ll pay next time we eat together.

Low-Risk Skill Practice – Bridging

- Practise with people you work with infrequently or non-intensively.

Work hard to get beyond abstract ideas and into the person’s underlying beliefs or feelings. Paraphrase and seek a thorough understanding of the other person’s position before presenting your own. Focus people’s attention on your need to understand or be helped.

Help me understand why you’re taking such a hard-line position on this issue.

I’m not sure I understand how you reached that conclusion. Can you describe your thinking to me?

- Practise in situations where you are flexible about results.

Use Bridging to influence others to work with you toward solutions you both can accept.

In your opinion, how can my department help your department speed up the loan approval process?

- Ask for help in solving problems when you feel doubtful or blocked.

Use Disclosing or Involving to elicit the person’s ideas, point of view, or experience. Remain flexible on how you will use their ideas to solve the problem. If the person suggests a promising approach, involve and listen until you hear a specific idea you can use. Then disclose that you find the idea valuable and that you intend to use it.

I’m having trouble working out these numbers. Can you show me how you calculated your solution?

- Involve and listen in meetings as often as you can.

Take initiatives to influence others. Count the number of times that you engage people who are inactive. See how often you can summarise a complicated, lengthy, or rambling discourse neatly and accurately.

Anne, I’d like to hear your ideas about this. You have more experience than I do. What are you thoughts on the issue?

Let me interrupt to see if I’m getting your point. This issue isn’t easy for me to grasp.

- Express understanding and empathy when service personnel are busy or harassed.

You seem to be having a really busy day today.

- Ask for information about a product and how to use it, or ask for help if you are uncertain about something.

Which phone do you think is the better value for the money?

Can you tell me anything about the reliability of this product? I’ve never owned one before.

How does this spreadsheet work? I seem to have scrambled my formulas.

- Find out more about the person.

Ask how long the person has been working or doing business, or ask how business is going. Look for opportunities to personalise the situation by Involving, Listening, or Disclosing.

I’ve always wondered what it’s like owning your own business. What’s it been like for you?

I hear you’ve been working two shifts. I don’t know if I could handle it. That must be hard for you to do. What do you do to make it easier?

I don’t think I could remember all those lines. How do you go about memorising a script?

- Ask for help, opinions, information, guidance, and advice.

You do not have to follow the advice, but let others know when you do.

I’m a little confused. There are so many types of running shoes here. Could you give me some guidance? You have a lot more experience than I do.

- Casual meetings, parties, or trips are ideal situations for practising Bridging.

Show an interest in what others say. Ask discreet questions and show that you understand and accept the answers. You may learn some extraordinary information. Act as a catalyst among strangers. Introduce those on your right to those on your left. Help them talk directly to one another.

Marge, my friend Dave is thinking of going to Italy. I know that you just got back. What suggestions do you have on where he might stay when he’s over there?

- With family or friends, pick a chronic area of disagreement and admit that you may be wrong.

Ask for help in understanding the other person’s point of view. If a past discussion ended in deadlock, paraphrase your understanding of where things stand. Try to get the conversation moving again by Disclosing that you were wrong, or by Involving to hear more about the other person’s position. Try to focus on the parts of the problem first. This will help you see the big picture later.

I’ve been thinking it over and I feel like I may have overreacted to your suggestion. I’d like to open up the topic again and hear you out.

- Talk to strangers.

Be careful not to be pushy. Give them an opportunity to talk about themselves too.

I notice you brought an umbrella. Did you hear the weather report today? I forgot to listen.

- Routinely ask for more information.

Ask people to tell you more about their opinions, points-of-view, or suggestions before expressing your opinion. Help them articulate the idea in more detail so that both of you can fully understand it. If necessary, intervene to prevent people from evaluating or rejecting an idea prematurely.

I’m interested in how you juggle so many projects at once. Can you tell me more about your approach to time management?

- Be open and forthcoming with information that might make you less threatening to others.

Tell more about yourself than usual. Describe a weakness as well as a strength. Share mistakes that you have made in similar situations.

You’ll have to be patient with me. I have a strong tendency to have rigid opinions about this issue.

Low-Risk Skill Practice – Attracting

- Identify common interests, similar backgrounds, or points of view.

You might begin with side issues or issues of marginal importance to the business relationship, then gradually explore riskier topics.

I noticed your class ring. You went to the same school I did.

You took this photograph at my favourite spot in the city. I imagine you really enjoyed being there.

I heard you mention that you just returned from a training programme. I attended one last week as well.

- Play ‘who do you know?’

Identifying common acquaintances is one of the safest ways of building connections.

Did you study with Professor Lopez by any chance?

I have a good friend who worked in that department when you did. Perhaps you knew her.

So, you’re from Falmouth. My brother introduced me to several people there when I visited him. Maybe you know one of them.

- Spend several minutes asking visioning questions before meetings.

What’s the best outcome that we could hope for in today’s meeting?

- Share your vision of the meeting’s outcome.

Let your imagination explore possibilities so that you can envision results beyond the mundane outcomes of most meetings. See if you can formulate a vision that really could happen, or a possible outcome that energises and interests you. Commit yourself to making it happen.

You know we’re capable of doing more than working on this one difficult issue. I can see us ironing out all the details together and finally signing the contract today. We’ll even have time for a small celebration!

- Share personal information with the people serving you, and make it easy for them to do the same.

You may discover some fascinating beliefs, values, or experiences that you have in common with people that you previously viewed only in their service roles.

I used to work at a supermarket too. I really liked the people I met there. Of course, when you work with the public, you see all kinds of behaviour. It can be a fascinating view of the world.

Tell me about that pin you’re wearing. It looks like one my mother wore.

- Listen to other peoples’ conversations and share any common experiences you may have had.

Perhaps you have seen the same film, visited the same area, attended the same concert, sports event, parade, or other activity. Try to compare experiences and establish common ground.

I overheard you talking about the new exhibit at the museum. I went yesterday, too, and really enjoyed it. What was your reaction?

You obviously enjoy your grandchildren. I have two who are about the same age. My whole perspective on life has changed! What about you?

- Try to get people excited about what you are doing or thinking — a project, holiday, trip, and so on.

Think about how you can best present your thoughts and ideas to excite them. Use words and images that are colourful and compelling. Try to communicate your enthusiasm.

I had an inspiration this morning. I suddenly saw the two of us in that sailboat, skimming across the waves, taking the wind hard in my face, and getting splashed with that cool water. The sun was bright, there wasn’t a cloud in the sky, and we were overflowing with excitement.

You know, I’ve always wanted to have a cherry tree in the garden. We can make that happen. I can see us picking out a sapling and finding the ideal spot to plant it. Imagine every year we can enjoy sharing one of the earliest and most beautiful signs of spring. And the cherries — I can just taste them.

- Try getting family members or friends to plan and carry out an activity together.

Take the lead. Try to identify a value or interest that you all have in common. Pick an activity based on that value, such as exercising, trying new foods, travelling to new places, and so on. Try to get them interested in participating. Increase your enthusiasm by imagining how much fun, useful, or productive it will be. Then share your fantasies with them. Try to make everyone feel that if you all get involved you can create a really exciting event.

As we were talking about that sailboat race, I realised that this is an interest that everyone in the room has, though none of us is a sailor. I have a fantastic idea. We could all go together to the river tomorrow morning and watch the boats. We could prepare picnic lunches and bring cushions and blankets. It will be a beautiful day, and sitting out in the breeze will be wonderful. We’ve all talked about how we should get outside more often. Now we can spend time outdoors and have a great new experience too!

Low-Risk Skill Practice – Disengaging

Postponing

- When you need more time to prepare, delay a meeting or appointment until conditions are more favourable.

I know we expected to meet tomorrow at 9am, but I’d prefer to wait until the next day. By then, I’ll have all the data you’re asking for.

- Do not insist that others meet with you if they are not ready or are under stress.

It sounds like you’re in a difficult spot. Let me change your meeting until next Tuesday at 3pm.

Giving and Getting Feedback

- When a meeting or discussion is not going well, step back from the situation and try to change it.

We’re having trouble making progress. I wonder if there’s another way we can work on this problem that’ll be more productive?

We’ve stopped listening to each other and are just repeating the same old arguments. Why don’t we spend some time looking for a different approach that we all can live with?

- Try to mediate arguments or confrontations that you are not a part of.

Be the cool one when others feel upset or angry. Help defuse the tension, but acknowledge the legitimacy of others’ feelings.

Everyone’s talking all at once and no one’s really listening. Let’s go around the table and give everyone a chance to express an opinion one at a time.

Changing the Subject

- In meetings, try not to react to caustic comments or irritations.

Use humour or other diversions to lessen tension, emotion, or conflict. When people focus on differences, emphasise areas of agreement and common goals to steer the subject in a positive direction.

It’s really clear that we both feel this issue is critical. We’ve done a lot of work listening to each other. We agree on many points and we’ve built up a lot of momentum. I can see us solving this issue successfully, beyond our expectations. Let’s put our heads together on another issue now and see how far we can go. I bet we’ll hit our stride right away. When we come back to the issue you just brought up, nothing will get in our way.

- Return to an earlier point, or start another line of discussion when energy decreases or people feel blocked and frustrated.

You had an idea earlier that we didn’t pursue. I suggest that we go back to it now and return to this point later.

Taking a Break

- When you feel yourself getting overloaded, tell the other person that you want a few minutes to work alone.

I need to go back to my office and read your proposal. If you can give me about an hour, we can get back together and I’ll give you my decision.

- Look for physical signs of fatigue or stress.

I notice that we’re all out of coffee and it’s been over two hours since we started working. Let’s take a break for ten minutes.

Postponing

- Try not to argue or respond impatiently when others are unreasonable or provocative.

Disregard evaluative statements, and do not respond judgmentally. Express willingness to work on the issue, but only if everyone is calm and polite. Model the behaviour that you want others to use.

I suggest that we discuss this tomorrow morning when we’ve both had a chance to cool off. We’re so upset with each other right now that there’s no way we can agree, anyway.

Giving and Getting Feedback

- Intervene in arguments.

Try to calm people down and help them deal with issues rationally. Avoid taking sides in the argument. Help the parties identify areas of agreement and specify areas of disagreement.

You and John agree that it’s important to limit the children’s screen time to one hour per day. What you don’t agree on is what they should watch. I have a suggestion. Why don’t you both write down five shows that you think are suitable and see if any of your choices overlap? Those can be the programmes that you let the kids watch.

Changing the Subject

- Encourage people to focus on one issue at a time and return to the most difficult issues later.

Try to define optimal conditions for dealing with the most difficult issues. Suggest that people handle these issues after they have rested or had time to think them over.

We still haven’t resolved the issue of whether or not to sell the house and move to a smaller apartment. It’s such an important decision that we really should deal with it when we’re both fresh and alert. Tell me what happened in your big meeting today.

- Stop heated or difficult discussions when they become painful or stressful.

Take a short break. If possible, do this with your partner. A joint excursion into a new topic will do wonders — it will cool you down and lead to creative breakthroughs.

Hey, let’s talk about the schedule for tomorrow. We’ve made some progress on the agenda today. Maybe if we look at the work ahead of us it will reduce the pressure.

Taking a Break

- Do not struggle to reach an immediate solution when you reach a block.

Let’s go for a walk and watch the snow fall. We can try to balance the books again when we get back.

- Recognise that intimacy may prevent you and another person from solving a serious problem together.

We’re too close to this and to each other to solve this problem without personal reflection — alone. Let’s take small breaks every 15 minutes and then come back to the problem together.