Understanding each Style

Persuading

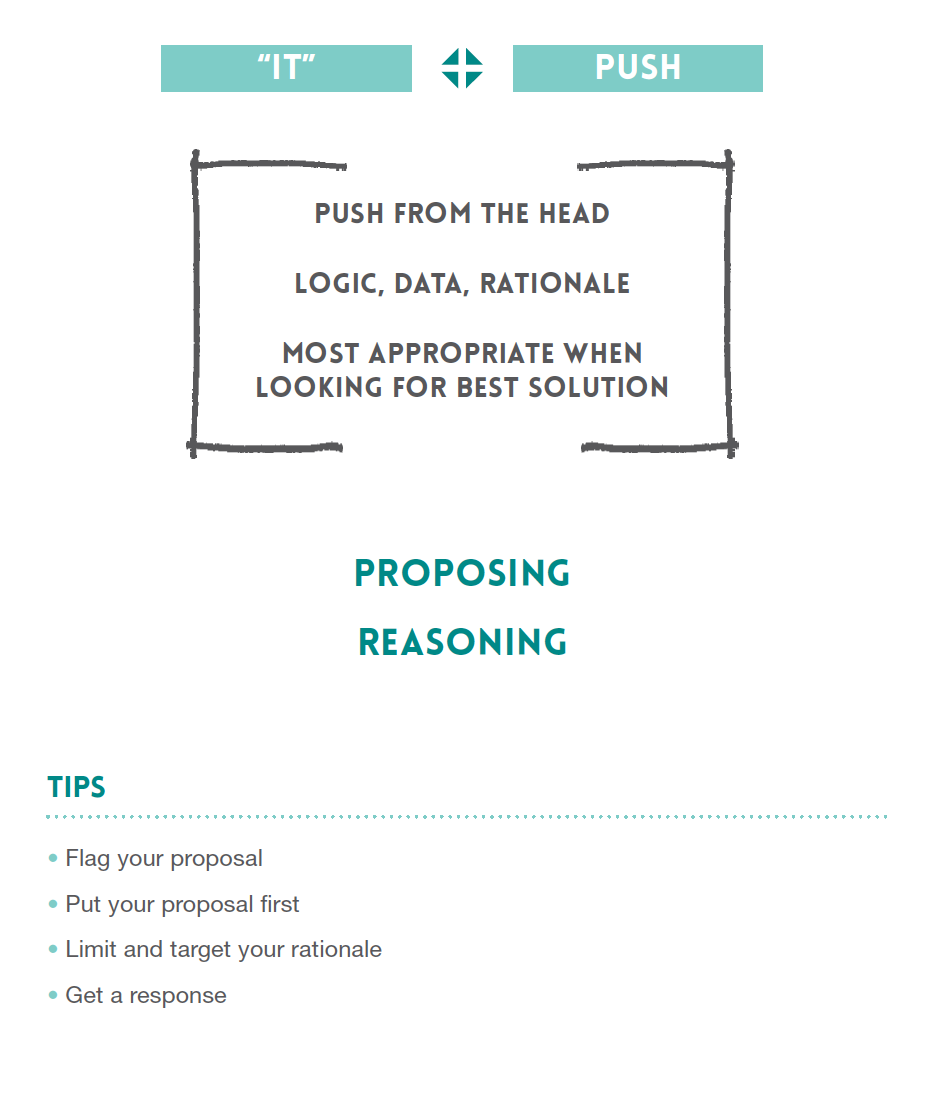

Proposing • Reasoning

The ‘It’ Style

Persuading comes from the head. It is about logic, data, and rationale. You effect change because of what you think and what you know.

Works best when you and the other person are willing to let facts determine the best course of action.

When you use Persuading well you encourage others to objectively review the available information and think logically about a solution.

Persuading comprises two Behaviours: Proposing and Reasoning. These two Behaviours used together and in this order, are very effective.

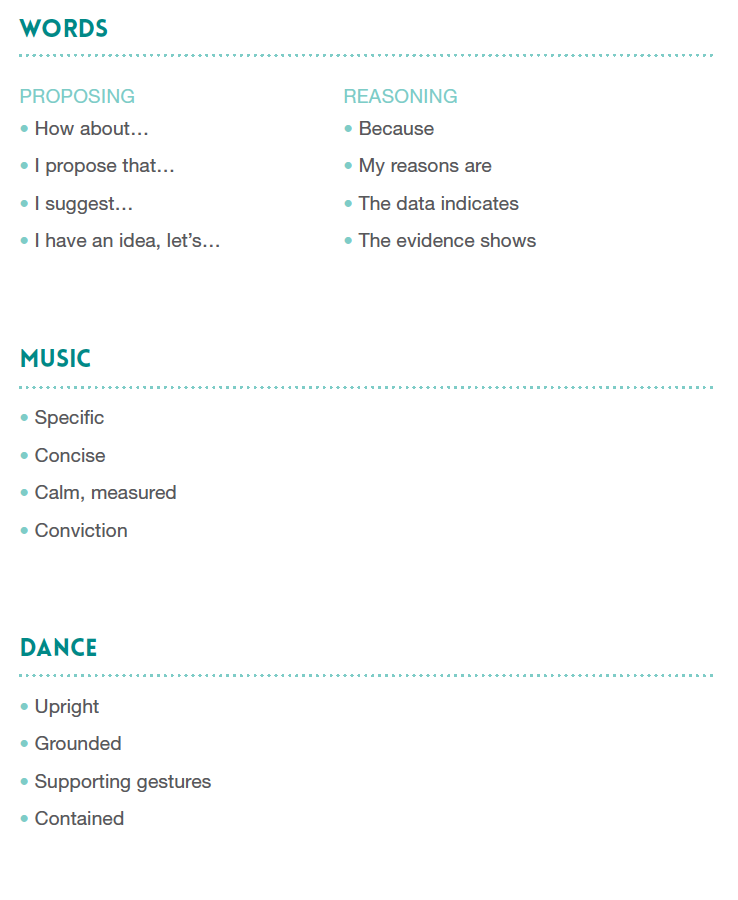

Proposing

Proposing is a recommendation for the best course of action. When you use Proposing well you make it clear to others that you are looking for a solution, rather than just a discussion about the data

Reasoning

You Reason by giving others facts that support your proposal. To Reason well you should give others two or three facts that are most likely to influence them.

Performance Guidance

- Put your proposal first to get attention.

- Be specific. What do you want to happen next?

- Only add detail if that adds value for the other person.

- Tailor your reasons to the other person.

- Know when to stop! Persuading is best done in smaller, concisely presented bites.

- Engage the other person in a full exchange of information and data.

Example

‘I recommend that you complete the report and get it to me by 5pm on Friday, and I have a couple of reasons. Firstly, that will give me the weekend to read the report so that I can prepare for the meeting on Monday. It will also mean that you can go off on your holiday next week knowing that there is nothing outstanding.’

Persuading – Further reading

Background

As children, we learned that facts, figures, logic, and reason are important forces for change. We discovered the power of rational argument in getting people to agree with us.

In turn, we learned from others when they had new information or data that contradicted our view of the world. We learned the personal satisfaction of intellectual exchange; some of us chose debating as a hobby or even a career. Above all, we discovered that factual decisions and rational agreements could help us meet our objectives and form strong and productive relationships with others.

Impact on others

Persuading is PUSH energy based on facts and logic. It involves two key Behaviours: Proposing and Reasoning.

People do not always respond to problems with logic. Instead, they base their reactions on intuition, feelings, or personal judgment. Perhaps they do not realise that a problem exists, so they fail to think about the facts or data surrounding it.

Persuading encourages others to think, analyse, and join in rational dialogue. It brings facts to the foreground and encourages thoughtful consideration of this information.

Persuading appeals to our need to behave logically and to respond to evident problems or realities with objectivity.

Persuading has a positive impact both during and after the influence attempt. By using logic, you set a tone and create a climate for rational treatment of the problem at hand.

By analysing the situation objectively, you set the stage for continued testing of the facts and evaluation of results with sound criteria and standards. Persuading supports the systematic and logical implementation of next steps after the influence attempt.

Your use of Persuading will prompt others to assume that you are open to influence by the data and logic they can present. Your decision to advocate your Influence Objective as a rational proposal invites others to assess that proposal rationally — so do not be surprised if others respond with counterproposals or alternative analyses of logic and reason.

Appropriate use of Persuading

Persuading has the highest impact when:

- You and the other person are willing to be objective.

Many problems are subjective. They do not involve hard facts or they do not respond to logic. Persuading is most effective in situations that appeal to objective reason. It is not as effective when strong intuitive opinion or personal judgment is driving the issues.

- Relevant, hard facts are available.

Without specific, comprehensive, and verifiable facts about the situation Persuading cannot have a strong impact.

- The situation is more cooperative than competitive.

When you or the other person have a high personal stake or vested interest in winning, the climate may not support calm, thoughtful, rational analysis. The other person may suspect your motives or assume that you have a hidden agenda, even if you do not.

- Alternative positions can be tested by facts and logic.

The other person may respond to your data with the challenge to prove it. You have a major advantage when you are able to do so. Your ability to weigh the facts on each side, offer options for testing, or demonstrate the weight of your evidence will add great power to your proposals and reasons.

- You control exclusive information.

If the other person has exclusive information that you do not have, you will be at a distinct disadvantage when Persuading. Conversely, when you have exclusive data that the other person does not have, you will have more power than the target — after all, knowledge is power. Persuading will be effective only if you use that power positively.

- You are respected as an expert in the situation.

The person who does not view you as a competent authority is likely to argue or doubt you based on your perceived lack of expertise. Persuading is strong especially in situations where you have credentials as an expert or can establish such credentials.

- You are viewed as wanting a rational solution.

Effective Persuading demands that you be reasonable. You must be willing to listen to the person’s data and counterproposals as rationally as he or she listens to yours.

- You and the other person’s emotions are under control.

The continued use of facts in emotionally charged situations is likely to inflame resistance and make rational agreement impossible. Because facts do not change feelings, Persuading is not a good Style to use when emotions run high.

Note: Facts are sometimes biased by the observer. When deciding whether or not to use Persuading, assess the true facts of the situation, not facts that have been distorted by your own biases. Be prepared that facts to you may merely be opinions to others.

Effective Performance of Persuading

- Balance your Behaviours: use proposals and two or three reasons.

Use the Persuading Style completely by stating both a proposal and two or three reasons. When you state a proposal but no reasons, you risk losing control of the argument. When you state compelling reasons but no proposal, the other person may reach a conclusion other than the one you intended.

- Structure the presentation as an influence event. ‘Label’ and outline your Behaviours.

Let your targets know that you are trying to influence them. Tell them that you will be making a proposal and giving reasons for it. There is so much factual noise in day-to-day life that you must make clear that you are actually trying to influence the target, not just chit-chat or pass information.

- Be specific, direct, and concise; eliminate qualifiers.

Generalised proposals and reasons may lead to vague reactions or commitments by the target. Lacking specific direction, the conversation will drift off course as energy is wasted in irrelevant discussion rather than focused exchange. Too much detail may impede momentum just as too little information will. Keep your outline in focus and add detail only when it will have real value for the target.

- Tailor your reasons to the target.

Do not assume that the other person thinks exactly the same way you do. Everyone’s rational processes develop out of personal nature and experience, so reasonable people will differ. Failure to recognise the target’s concerns may lead to argument or gridlock. Make your proposals and reasons compelling to the target: anticipate the other person’s rational priorities and way of thinking.

- Recognise the limits of logic.

People’s capacity to absorb and process new information is limited by their interest, level of resistance, and energy at the time you present it. Protracted Persuading can result in loss of energy and momentum. Persuading is best done incrementally in smaller, concisely presented bites.

- Beware of argument dilution.

Do not dilute your argument by giving lots of reasons — quantity is a poor substitute for quality. By giving numerous reasons, you make yourself vulnerable to attack on your weaker points. Instead, present two or three strong reasons and modify or add to them to fit the other person’s response.

- Encourage active debate: emphasise rational exploration of issues.

The purpose of Persuading is to reach a rational solution to a problem. This requires engaging the target in a full exchange of available data. When the target fully participates, he or she is more likely to be convinced — and to work hard to implement the solution as well. Persuading should be two-sided, not one-way.

Persuading Example: Overdue Report

The following example demonstrates the use of Persuading in a conversation between two managers. Margaret is the manager of a department that prepares business forecasts. Sam is the manager of a department that compiles raw data into standardised monthly reports on the company’s year-to-date sales performance. Margaret needs Sam’s sales reports to prepare her business forecasts. This month, Sam’s report is late. This is not the first time Sam has missed a deadline. Margaret has asked to meet with Sam to discuss the problem. Her objectives are to influence Sam to complete his business forecast by four o’clock this afternoon, and to develop a plan for meeting future report deadlines.

PART ONE

Margaret: Sam, I suggest a quick progress review of that sales report you’re working on. Now, the schedule says it was due this morning, and I need to get the next step done before the two o’clock management committee meeting tomorrow. Let’s take a few minutes to discuss it.

Sam: Well, I’m afraid the report’s going to be a little late, Margaret, because I had some last-minute problems that I didn’t expect. But I will get it to you as soon as I can. I’m heading back to my desk right now. Maybe we can talk a little later.

Margaret: Sam, I suggest we talk about it now. The management committee meeting is at two o’clock tomorrow afternoon. That’s thirty hours from now. Now, with some sensible planning, the report can be done on time and I can work your numbers into my business forecast.

Sam: Okay, okay, tell me what you have in mind.

Margaret: Well, Sam, I suggest that you get your report to me by four o’clock this afternoon.

Sam: Four o’clock?

Margaret: Yes. Let me explain why. It’ll take me at least five hours to complete my business forecast once I get your numbers. Then I can work late tonight and organise the final forecast, type it up, and make some copies. Now, that way, the forecast will be ready with plenty of time for me to review and proofread tomorrow morning. I’d even have a few hours to absorb the data before I make my presentation.

Sam: Look, Margaret, I’ve got a basic problem here, and that involves the numbers I got from the field. You see, I thought I’d be on schedule this time. But when I reviewed the data a few days ago, I realised that some of the numbers were wrong. So, I had to phone back the sales organisation for corrections. Now I have to redo all my calculations. That’s going to take some time.

Margaret: Okay, well, then I suggest you lay it out for me — all the steps it’ll take to get the report done and how long each one will take.

Sam: Well, okay. Let’s see, in terms of steps, I guess the first thing I need to do is cross-check the numbers. But, ah, I don’t know, four o’clock, Margaret. That’s cutting it close. I still don’t think I can get it done by then.

Margaret: Now, Sam, think through all the steps before deciding that you don’t have enough time. Once you get all the tasks laid out, it might turn out that the report won’t take as much time as you think.

Sam: That’s optimistic of you, Margaret. But, ah, I know I can’t do it unless I get some help and at this point I don’t know who could jump in and really be useful.

Margaret: I know that’s the way it looks, but consider setting aside the resource issue for a minute. Let’s deal with one thing at a time — use a logical approach — you know, set your feelings aside for awhile. What’s your estimate on how long the cross-checking will take?

Sam: Oh, something like ten hours, you know, I have the data from ten regions — so about an hour a region.

Margaret: Okay, then what? List all the steps.

Sam: Okay, ah well, then the calculations will need to be done. That will take about two hours worth of data entry time. The spreadsheet I can do in about an hour. Text summary graphs — about two hours. Ah, and then an hour for final proofing and printing.

Margaret: Okay. Now add it up and see how many hours it’ll take.

Sam: Okay, well, let’s see, ten, 12, 15… about 16 hours total.

Margaret: That’s with one person doing the work.

Sam: Yeah. Me.

Margaret: Well, that puts you beyond the four o’clock deadline and it puts a lot of pressure on you too. So now let’s look at the resource problem. Now, I think it makes more sense to spread out the workload. Not every task needs your personal attention and I know there are a few people available to help out. So, I suggest blocking out what you have to do and what other people can do. If you analyse the tasks and figure out who can do what, you should be able to find a reasonable solution.

Sam: Okay, well if we could get three people to do the cross-checking on the numbers simultaneously, then we could conceivably get this done in what, three hours?

Margaret: There you go.

Sam: I could do the calculations and the spreadsheet, while someone else is setting up the graphs, and that would cut some time off…

PART TWO

Narrator: Through some additional problem solving, Sam and Margaret figure out a way to meet the four o’clock deadline by using some staff members from each of their departments. Now, Margaret will use Persuading to influence Sam to get his reports done on time in the future. Notice how she uses Persuading at the end of the conversation to disengage.

Margaret: Sam, I have another suggestion. Why don’t you set up a work plan for getting these reports done on time in the future? Now, let me explain why. Your reports have come in late twice in the last year. One of those times, the management committee got an incomplete forecast from me and without all the data they needed. The second time, I had to ask the managers to postpone the meeting, which…

Sam: …caused us to take a lot of flak. Yeah, I know, I know.

Margaret: That’s right. And this situation has been a close call too — you’re right down to the deadline again.

Sam: Yeah, I hate being hit with these unexpected problems that take so much time to fix.

Margaret: Well, that’s a good reason to have a work plan. It would give you some early warning if there were problems like you just went through — getting incorrect data from the field. You could build in some extra troubleshooting time to fix the problem. So, what do you think? Tell me if a permanent work plan makes sense to you.

Sam: Well, yeah, of course. I’d be willing to develop a plan. But we really need to get the field organisations on board too.

Margaret: Okay, point taken. Tell you what, Sam. I suggest you take one step at a time and focus on getting this report done first. Then afterwards you can work on developing a work plan, using this experience as a reference point.

Sam: All right, all right. That makes sense to me.

Margaret: How about we discuss it further at lunch tomorrow?

Sam: Fine. Lunch it is. For now though, let me get on with this report. I’ll get back to you with my data at four, maybe five — let’s see how it goes with my number crunchers, okay?

Margaret: Okay, Sam, thanks.

Persuading Example: Videos

STYLE: Persuading

BEHAVIOUR: Proposing

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid / Off the Cliff

Summary:

Trapped and outnumbered, Paul Newman proposes the only possible escape route.

Excerpt:

Butch: No we’ll jump.

Sundance: Like hell we will.

Butch: No it’ll be ok. If the water’s deep enough and we don’t get squished to death. They’ll never follow us.

Sundance: How do you know?

Butch: Would you make a jump like that you didn’t have to?

Sundance: I have to and I’m not gonna.

Butch: Well we have to otherwise we’re dead. They’re just gonna have to go back down the same way they come. Come on.

STYLE: Persuading

BEHAVIOUR: Reasoning

The Hunt For Red October / Another Possibility (NOTE: MILD SWEARING!)

Summary:

Alec Baldwin presents evidence to support his theory that a Russian sub captain might be trying to defect.

Excerpt:

Ryan: I was just thinking that perhaps there’s another possibility we might consider: Ramius might be trying to defect.

General: Do you mean to suggest that this man has come . . .

Pelt: Proceed, Mr Ryan.

Ryan: Well, Ramius trained most of their officer corps, which would put him in a position to select men willing to help him. And he’s not Russian. He’s Lithuanian by birth, raised by his paternal grandfather, a fisherman. And he has no children, no ties to leave behind. And today is the first anniversary of his wife’s death.

Persuading Exercises

Exercise 1

Select a group member who is deciding whether or not to hire you for a job. Propose what you could do if you were hired. Support your claims with facts and logic. The other member should question your position forcefully. Continue to use Persuading, tailoring your argument to the specific resistance you hear.

Exercise 2

Get another member to play the role of your real-life manager. Use Persuading to get him or her to give you more responsibility and freedom in your work. Be specific in your Influence Objective. The other should moderately resist your attempt at first and then allow you to use Persuading as he or she feels influenced.

Exercise 3

Present your position on a current political or social issue. Another member of the group will attack your position and ask searching and difficult questions. Defend your position vigorously, but stay in Persuading. Rebut your opponent’s argument with specific counter proposals and the facts to back them up.

Exercise 4

Try to convince another member of the group to do something that you believe would be good for him or her (for example, change diet, initiate or change an exercise routine, alter a habit, or do some extra programme study). Use Persuading to convince this person to take an action step today. Focus your proposals and reasons on the specific resistance you encounter.

Exercise 5

Use Persuading to convince another member of the group to spend time with you later today reviewing your ISQ analysis and comparing its results with your performance in the Tracks. The other person may resist or ask questions based on his or her real concerns. Tailor your proposals and reasons to the other’s specific situation and resistance.

Exercise 6

Select a group member to play the role of an actual person with whom you work (manager, colleague, direct report, client, and so on). Identify one thing that this person is doing or not doing that significantly reduces your productivity. Use Persuading to convince this person to change this behaviour in a positive way. The other person should resist you as the actual person would. Fit your arguments to the specific objections and resistance you hear.

Exercise 7

Your colleague in another department attends the same coordinating meetings you do. While you get along well together personally, this person behaves unprofessionally in the weekly coordinating meetings that involve others. Specifically, your colleague gets angry and upset when others disagree with him or her. Use Persuading to convince your colleague to change this behaviour.

Exercise 8

Your manager has made some recent decisions that have caused your group to lose much-needed administrative support, but without consulting you in detail. Use Persuading to convince this person to involve you more significantly in the next round of decision making. Your manager will resist without becoming dictatorial.