Objectives and Background

Your group is the salary committee of the Enterprise Corporation. Your task is to allocate the sum of money that has been budgeted for salary increases among the available candidates. The total sum available depends on how many people there are in your group.

Each member of the committee represents a candidate who is their direct report. Negotiate the best outcome you can for your candidate using all of the available information. Your candidate expects you to secure a salary increase and you will lose credibility within the organisation if you fail to do so.

You are prepared to deadlock if you cannot reach an agreement that is acceptable to you. However, deadlock will carry a personal cost. The president of Enterprise is clear that failure to resolve conflict and set salaries will be reflected in your own performance review, including your bonus. You can’t afford a career setback, given the current economic climate. You need to find a way to get what you think your candidate deserves.

At the end of the exercise you will make a comparative assessment to determine how well you have performed for your candidate against previous programme participants.

At the time of the discussion the environmental factors are:

- Inflation running at 5%

- Economy emerging from 36-month recession

- Enterprise profits ahead of competitors but significantly down on previous year

- Enterprise needs to maintain competitive edge by increasing productivity and reducing costs

Instructions

Step 1: 15 minutes

Select a candidate to represent. Select a candidate before reading their description. If you have fewer than six committee members, drop the last candidates on the list.

Read the information about your candidate first, then read about the others.

Set a clear influence objective based on the Influence Dollar (ID) increase you wish to get for your candidate as well as any other results you hope to attain.

Step 2: 15-30 minutes (depending on size of group)

As a group distribute the total budgeted salary allowance among all the candidates.

- 3 members – ID 6490

- 4 members – ID 9090

- 5 members – ID 10910

- 6 members – ID 12985

If you have fewer than six group members, reduce your 30-minute negotiation period by 5 minutes for each member short of six.

All members must be willing to go along with the final distribution. If the group fails to decide in the time allotted, then none of the candidates will get a pay increase.

Candidate Descriptions

Ann Martin

Role: Manager, Data Processing Department.

History: Joined Enterprise 14 years ago at entry level

Salary: Currently ID 46,800; received ID 2,250 salary increase 18 months ago.

- Excellent relationships with subordinates and peers.

- Has reduced volume of complaints and personnel difficulties in the department.

- Technical innovator; recently supervised complex software conversion project completed before deadline.

- Uncomplaining, but formally requested salary increase citing recent cost of living increases and her tenure with the company.

Elsa Bostrum

Role: Plant Maintenance Superintendent; Certified Mechanical Engineer.

History: Joined Enterprise 10 years ago. First senior female engineer promoted to management; viewed by other female technical staff as a role model.

Salary: Currently ID 41,500; received ID 2,700 salary increase last year.

- Hard-working, ambitious, and determined; inventive at solving mechanical and management problems.

- Recently proposed a solution to a serious production bottleneck; disappointed when implementation was postponed due to poor cash flow.

- Installed one of the industry’s few effective incentive systems for maintenance workers, saving Enterprise ID 300,000 annually in repairs and lost production time; awarded last year’s raise partly in recognition of this accomplishment.

- Presents her incentive system at conferences, resulting in favourable notice to herself and Enterprise.

- Approached by competitors about potential job opportunities; has only hinted at possibility of leaving Enterprise.

- Company considering her for a non-engineering management post; would be very inexperienced in this position, but her intelligence and adaptability qualify her.

Jamie Wallace

Role: Human Resources Manager, Production Plant.

History: Joined Enterprise 3 years ago

Salary: Currently ID 41,500; received ID 2,000 salary increase last year. Their predecessor’s final salary was ID 43,200.

- Hired to introduce modern personnel methods and systems; has since completely transformed personnel operations.

- Competent, dedicated, and widely respected; Their energy and drive in initiating change has alienated some older line managers.

- Has impressively outperformed their predecessor, who left the personnel records and procedures in severe disarray.

- Deeply committed to equal pay for LGBTQ+ employees; has campaigned hard and with limited success for upgrading LGBTQ+ employees’ status in the company.

- Active in professional affairs outside the company; is an influential member of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

Max Eberly

(use only with groups of 4, 5 or 6)

Role: Design Engineer.

History: Joined Enterprise 2 years ago

Salary: Currently ID 52,000; received ID 4,300 salary increase last year.

- Recently secured three patents; two resulted in important and very profitable additions or modifications to the Company’s main product line.

- An inspired and original thinker.

- Regarded by some as temperamental, single-minded, and combative about his ideas.

- Perceived by some as an individual contributor, not a team player, making it difficult for them to work with him in groups.

- Recently mentioned to colleagues a job offer from a competitor for ID 55,000 per year.

José Peralta

(use only with groups of 5 or 6)

Role: Customer Service Engineer.

History: Joined Enterprise 4 years ago when there was a shortage of customer service engineers

Salary: Currently ID 36,400; 10% less than other qualified customer service engineers. Received ID 1,450 salary increase last year.

- Has completed technical training; currently as technically qualified as other customer engineers in the field.

- Considered one of the company’s best engineers; customers and associates praise his energy and drive.

- Pleased with the opportunities company has provided, but dissatisfied with remuneration.

- Feels that he has not received equitable treatment on pay raises; has hinted that he would likely be treated more fairly if he did not belong to a minority group.

- Quality performance and high commitment may suffer if this situation is not corrected; could become an angry and embittered problem employee.

Thomas Schmidt

(use only with groups of 6)

Role: Controller, Production Division.

History: Joined Enterprise as a graduate

Salary: Currently ID 41,500; his last raise was ID 1,800 a year ago.

- Manages a small group of accountants and clerks.

- Good performer: steady, reliable, accurate.

- Shy, awkward when under stress; formal and proper with a stubborn streak; however, direct reports never complain.

- Provides information to other departments with a minimum of trouble.

- Recently told production manager about a job offer received from an overseas construction company.

- Unclear about reasons for wanting to leave; mentioned ‘money’, ‘need for change’, and ‘greater opportunity for advancement’.

- Has no obvious replacement; departure would be highly disruptive.

- Manager wants to do everything possible to retain him, at least until a replacement can be found.

Review Instructions

Step 1: 5 minutes

- Independently review the Salary Exercise Performance Norms for the candidates.

- Compare your personal performance with that of previous participants who represented your candidate. Did you do better, about the same, or worse than past participants working with the same case?

Step 2: 5 minutes

-

Working independently, rank order the members of your group, including yourself, according to how effective each person was in their negotiation behaviour. Make notes on why you ranked each person the way you did.

Step 3: 10 minutes

- Working as a group, share your rankings, along with reasons. Avoid discussion at this time, except for purposes of clarification. Use the Guidelines for Giving and Receiving Constructive Feedback to help structure this activity.

Step 4: 30 minutes

- Review and analyse the exercise recording. Use the Tally Sheet to code the Styles and Behaviours you observe. Code yourself and one or two others. A volunteer should sit with her or his finger on the pause button, to halt the recording for discussion.

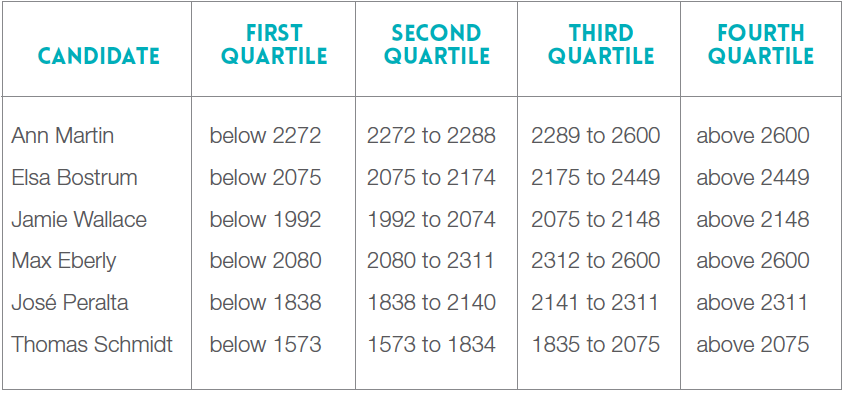

Performance Norms

Instructions

Find the row for your candidate in the table below. Reading across, identify the box which includes the salary you negotiated for your candidate.

The column heading directly above the box you identified will tell you how well you did for your candidate compared to past participants who have represented the same candidate.

The data is arranged by quartiles. For example, if the salary increase you negotiated falls in the First Quartile, it means that 75 to 100 percent of the other participants who have represented your candidate negotiated a higher salary than you did. If the increase falls in the Fourth Quartile, it means that the salary you negotiated for your candidate is in the top 25 percent as compared to past participants.

Discussion Notes

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

People who expect more and ask for more get more. Large initial demands improve the probability of success, but they also increase the probability of deadlock. While it is true that a deadlock is better than a bad deal, it is important to be able to break through deadlock to reach agreements which satisfy both parties. Deadlocks almost always have their own costs.

Concession will break a deadlock, but you will be less likely to do well unless you get something in return—a quid pro quo. Large concessions, the first concession, and last minute concessions will all detract from your success unless you make them contingent on a concession from the other side.

Compromise will break a deadlock, but compromise usually results in both parties getting less than they hoped for. Compromise agreements leave value on the table, and often are not as strong as other truly negotiated agreements. The tactic of splitting the difference may be a well-established institution for breaking deadlocks, but it represents a mutual agreement to settle for less. It may indicate Avoiding.

Alternative currencies of exchange can help break deadlocks by meeting the needs of all parties.

The use of negative power—either Forcing or Avoiding—weakens a negotiator over the long run. Trust is reduced and hostility is increased, destroying communication which is the keystone of any agreement process.

INFLUENCE STYLES IN NEGOTIATION

The Push Styles are most important in setting ground rules, making offers or demands, and contracting.

- Persuading is most effective when concentrated around two or three strongest points. Do not dilute the argument with weaker points that make you vulnerable to attack.

- Asserting is most effective when centred on Stating Expectations and Applying Incentives. Negative personal Evaluation and the use of Pressure tend to create attack/defend spirals that are unproductive, especially in conflict situations.

The Pull Styles are most important in setting a positive climate and exploring underlying needs.

- Bridging is useful in negotiating to:

- Build trust by selectively Disclosing motives, feelings, and privileged information.

- Collect information through questioning (Involving).

- Gain depth of understanding through Listening.

- Attracting is useful in negotiating to:

- Set a positive climate and optimistic outlook.

- Maintain momentum and reduce conflict by highlighting and emphasising Common Ground.

BUILDING COALITIONS

Even a very strong negotiator with a good case, but who stands alone, can become isolated and thus do poorly. In a multisided bargaining or negotiating session, success often depends on building coalitions.

Coalitions require trust to form and hold, and Bridging Behaviours are key to building trust. Those who appear to be too tough and exploitative may be isolated by others. A sensitive mix of Styles will hold the coalition together (for example, being strong and demanding while selectively supporting the goals and aspirations of some of the others).

AVOIDANCE IN BARGAINING AND NEGOTIATING

People who are not accustomed to bargaining and negotiating often engage in behaviour that turns the interaction into some other kind of process. This may make participants more comfortable, but it reduces learning about negotiation. It is Avoiding behaviour.

It is important to distinguish behaviour which is directed toward negotiation from behaviour directed toward conflict-avoidance for its own sake. Avoidance behaviour is used to reduce personal risk and involvement. Sometimes an entire group uses Avoidance to reduce conflict and tension. Listed below are some conflict-avoiding behaviours and approaches that we have observed when reviewing recordings of negotiations:

- Bureaucratic Avoidance: inventing or assuming a procedural model for making a decision that avoids having to argue one’s own case, make personal demands upon others, or experience feelings of winning and losing.

- “Poor Case” Avoidance: reading one’s case as inherently weak. In role-play exercises this is easily identifiable. In “real life”, it often takes the form of blaming people, places, and things for our less than favourable position. This form of Avoidance justifies conceding before really trying to negotiate for the best solution possible. The essence of effective negotiation is doing the best you can with the case or situation that you get.

- Corporate-Goals Avoidance: inventing or assuming some higher entity or set of values which deserves greater loyalty than one has to one’s own side or case in the negotiation. For example: “I really don’t feel that strongly about this in light of the company’s economic position”. This allows the participant to give in and make concessions without feeling like a loser.

- Social Justice Avoidance: accepting equal-rights or egalitarian solutions in the absence of any determination of individual worth. An example would be giving people an across-the-board increase of 5 percent as opposed to basing pay increases strictly on the merit or contribution of each individual.

It is interesting to note that two or more individuals, using any one of these Avoidance approaches, can reinforce each other and implicitly agree to mutual Avoidance. For example, someone who believes that they have a poor case will play quickly into the hand of someone seeking an egalitarian solution, and both will be available to someone else who has a bureaucratic procedure for resolving conflict. If another member is ready to place the company’s needs above all other considerations, then we have a group ready to Avoid on a grand scale.

Of course, the methods of avoiding conflict listed above are not restricted to training exercises. They frequently appear in one form or another in the work place.

We severely restrict our potential as negotiators when we create or accept a rationale which offers premature, superficial agreement in return for polite interaction. At the same time, we are failing to exploit the value of negotiation as a positive decision-making process. By settling for less, we serve neither ourselves nor the others who have a stake in the outcome.